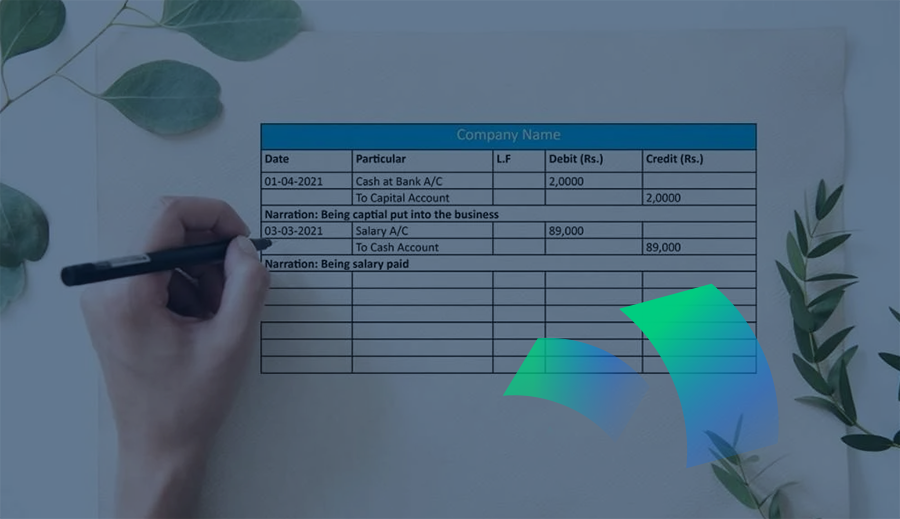

Journal entries are fundamental to recording a company’s financial transactions. But not every transaction is immediately final or straightforward, and adjustments are sometimes necessary to ensure accuracy and compliance with accounting standards.

Adjusting journal entries align the financial records with the actual situation at the end of an accounting period, making sure the books accurately reflect revenues, expenses, assets, and liabilities.

For accountants, especially financial controllers, these adjustments are a crucial part of the month-end or year-end closing process. Knowing what to adjust and when is key to maintaining accurate books and producing reliable financial statements.

In this post, we’ll explore what adjusting journal entries are, the different types of adjustments, when they’re needed, and how to make them effectively.

What Are Adjusting Journal Entries?

Adjusting journal entries are made at the end of an accounting period to update the balances of certain accounts before financial statements are prepared.

These adjustments ensure that the financial statements provide an accurate picture of a company’s financial position by incorporating revenues that have been earned but not yet recorded, expenses that have been incurred but not yet recorded, and assets or liabilities that may need adjustment due to timing differences.

Adjusting entries are typically made for the following reasons:

- To recognize revenues earned but not yet billed or recorded

- To account for expenses incurred but not yet paid

- To allocate the usage of prepaid expenses and assets

- To adjust the value of liabilities or accrued expenses

These adjustments follow the matching principle of accrual accounting, ensuring that revenues and expenses are recognized in the period they occur, rather than when cash exchanges hands.

When to Make Journal Entry Adjustments?

Adjusting entries are usually made at the end of an accounting period, whether it is monthly, quarterly, or annually. It is important to make these adjustments before preparing financial statements to ensure they reflect the most up-to-date and accurate information.

However, some situations may require more frequent adjustments. For example, companies with significant prepaid expenses or liabilities may need to make adjusting entries on a weekly basis to ensure accurate financial reporting.

Key times to make adjustments include:

- Before the preparation of financial statements: This ensures that the financial statements reflect accurate financial information, providing stakeholders with a true understanding of the business’s financial health.

- When preparing closing entries: Closing entries are made to zero out the balances of revenue, expense, and dividend accounts. Adjusting entries should be made before closing entries to ensure that all income and expenses are fully recognized.

- When significant transactions are not reflected: For example, if a business has delivered services in a particular period but hasn’t yet invoiced the client, adjusting entries ensure that the revenue is recognized in the correct period.

Types of Adjusting Journal Entries (With Examples)

Adjusting journal entries can be divided into five main categories: accrued revenues, accrued expenses, deferred revenues, deferred expenses, and depreciation (or amortization). Each type serves a unique purpose in aligning financial records with the actual events of the accounting period. Let’s take a closer look at these types, understand their significance, and walk through examples for each.

1.) Accrued Revenues

Accrued revenues are revenues that have been earned by providing goods or services, but the payment has not yet been received, and the revenue has not been recorded. This often happens when a company provides a service or sells goods on credit. Since the revenue was earned in the current period, it must be recorded, even if the actual payment will be received later.

Accrual accounting principles dictate that revenues must be recognized when earned, not when cash is received. Failing to make this adjustment would understate both revenue and accounts receivable in the financial statements, leading to an inaccurate picture of the company’s profitability.

Example of accrued revenue adjustment:

Imagine a software development company that finishes a project for a client on December 20th. The client agrees to pay $5,000, but the invoice won’t be sent until January 15th. Although the payment will be received in the next accounting period, the revenue was earned in December, so an adjusting entry is necessary.

Adjusting entry:

- Debit: Accounts Receivable $5,000

- Credit: Service Revenue $5,000

This adjustment ensures that the December income statement reflects the revenue earned, even though the cash will be received in January.

2) Accrued Expenses

Accrued expenses are costs that have been incurred but not yet paid or recorded in the company’s accounts. These expenses typically arise when services are received or obligations are incurred before the cash payment is made. Common examples include interest expenses, wages, and utilities.

According to the matching principle, expenses must be recorded in the same period as the revenues they help generate. Failing to record accrued expenses would result in understated liabilities and expenses.

Example of accrued expenses adjustment:

Suppose a marketing company owes its employees $10,000 for work done in December, but payroll won’t be processed until the first week of January. Even though the payment will be made in the next period, the work was completed in December, so the expense should be recognized in that month.

Adjusting entry:

- Debit: Salaries Expense $10,000

- Credit: Salaries Payable $10,000

By making this adjustment, the company accurately reflects the salary costs in the correct accounting period, ensuring that the expenses are matched with the revenues they helped generate.

3) Deferred Revenues (Unearned Revenues)

Deferred revenues, also known as unearned revenues, refer to payments a company receives in advance for goods or services that have yet to be delivered. Since the company hasn’t earned the revenue yet, the payment is initially recorded as a liability. Over time, as the company delivers the goods or performs the services, the revenue is recognized.

Without this adjustment, the company would prematurely recognize revenue for services it hasn’t yet provided, leading to an overstatement of both revenue and income. Deferred revenues help spread the recognition of revenue over the appropriate periods in which the services or products are delivered.

Example of deferred revenue adjustment:

A fitness center sells a 12-month membership for $1,200 on December 1st. By the end of December, only one month of service has been provided. The company cannot recognize the entire $1,200 as revenue because it still owes the customer 11 more months of service.

Adjusting entry:

- Debit: Unearned Revenue $100 (for one month’s worth of service)

- Credit: Service Revenue $100

After this adjustment, the income statement for December will reflect only the revenue actually earned, and the liability (unearned revenue) will decrease as the service is provided.

4) Deferred Expenses (Prepaid Expenses)

Deferred expenses are costs that a company has paid in advance for goods or services it will receive or consume in future periods. These prepayments are initially recorded as assets because the company expects to derive future benefits from them. Over time, as the benefits are realized (for example, as the prepaid services are used or consumed), the asset is reduced, and the expense is recognized.

Without this adjustment, the financial statements would misrepresent the company’s assets and expenses. Prepaid expenses that have been partially used must be recorded as expenses in the period when they are incurred to avoid overstating assets and understating expenses.

Example of deferred expenses adjustment:

A company pays $6,000 in advance for a 12-month insurance policy on January 1st. At the end of each month, $500 of that prepaid insurance is used. By the end of December, all 12 months will have been used up, so it is essential to recognize a portion of the prepaid insurance as an expense each month.

Adjusting entry (for the first month):

- Debit: Insurance Expense $500

- Credit: Prepaid Insurance $500

This entry ensures that only the portion of the insurance that has been consumed is recognized as an expense in each period.

5) Depreciation (or Amortization)

Depreciation is the process of allocating the cost of a tangible asset over its useful life. It reflects the wear and tear, deterioration, or obsolescence of fixed assets like machinery, vehicles, and equipment.

Amortization follows the same principle but applies to intangible assets, such as patents or trademarks. These adjustments help match the expense of using an asset with the revenue it helps generate over time.

Depreciation spreads the cost of an asset over several periods, rather than recognizing the full cost as an expense in the period when the asset was purchased. This approach adheres to the matching principle, ensuring that the expense of using the asset is recognized over its useful life, thus preventing overstated profits in the earlier periods when the asset was acquired.

Example of depreciation adjustment:

A company buys machinery for $60,000 with an expected useful life of 5 years. Each year, $12,000 of depreciation needs to be recorded to reflect the gradual reduction in the machine’s value due to use and wear over time.

Adjusting entry (for one year):

- Debit: Depreciation Expense $12,000

- Credit: Accumulated Depreciation $12,000

The accumulated depreciation account is a contra-asset account that reflects the total depreciation recorded over the years. This allows the company to show the machinery’s current book value on the balance sheet and accurately reflect the depreciation expense on the income statement.

How to Adjust Journal Entries

After reviewing the common types of adjusting entries, it’s important to understand the specific steps involved in making these adjustments accurately. Here’s a step-by-step guide to the process:

1) Identify the Accounts Needing Adjustment

Start by analyzing the company’s financial records to identify which accounts require adjustment. Look for transactions such as revenues earned but not yet recorded, expenses incurred but not yet paid, and items like prepaid expenses, unearned revenue, or accumulated depreciation. These are the most common areas that need adjustments to accurately reflect the company’s financial position.

2) Determine the Correct Adjustment Amounts

For each account identified, calculate the specific amount that needs adjustment. This step requires a clear understanding of the matching principle, which ensures that revenues and expenses are recorded in the period they are earned or incurred, not when cash is exchanged. For example, determine how much revenue should be recognized from unearned revenue or how much depreciation has accumulated over the period.

3) Prepare the Adjusting Journal Entries

Once the accounts and amounts are identified, record the adjusting journal entries. Each entry will include a debit to one account and a credit to another, following the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity). For example, if adjusting for accrued expenses, you would debit an expense account and credit a liability account. Ensure the entries accurately reflect the adjustments needed.

4) Post to the General Ledger

After making the adjusting journal entries, post them to the appropriate accounts in the general ledger. This step updates the account balances to reflect the adjustments, ensuring that all financial activity is properly recorded before the financial statements are prepared.

5) Review for Accuracy

Verify that each adjustment aligns with the financial transactions and complies with the company’s accounting policies and standards, such as GAAP or IFRS. This review ensures that the financial statements present an accurate and fair view of the company’s financial position.

Automate Your Adjusting Journal Entries With DOKKA Close

The process of making manual adjusting journal entries can be complex and time-consuming, especially when handling large volumes of transactions across multiple accounts. This is where automation can make a significant difference by streamlining the process and reducing the risk of human error.

Financial close automation tools, such as DOKKA, are revolutionizing how companies manage the financial close process, including the preparation and posting of adjusting journal entries.

DOKKA is an AI-powered close management platform designed to simplify and accelerate the financial close process. It integrates seamlessly with all major ERPs, and uses proprietary AI and machine learning to automate repetitive tasks like adjusting journal entries, account reconciliations, and document management. By reducing manual work and improving accuracy, DOKKA helps finance teams close their books faster and with greater confidence.

With DOKKA, companies can:

- Automate the capture and processing of financial documents.

- Easily automate the creation and posting of adjusting entries.

- Benefit from real-time collaboration tools.

- Centralize their close data into one place.

- Stay compliant and audit ready in real time.

Ultimately, automation tools like DOKKA not only save time but also improve the accuracy and transparency of adjusting journal entries, allowing finance teams to focus on higher-level strategic tasks rather than getting bogged down in manual work.