In the world of finance, where decisions are based on careful analysis and numbers are of utmost importance, there is one document that stands as a gateway to understanding a company’s financial health: the balance sheet.

Often considered the financial snapshot of an organization, the balance sheet unveils the intricate interplay between assets, liabilities, and equity and paints a comprehensive picture of its stability and potential.

Unravelling the balance sheet requires more than just a superficial glance at the numbers, it calls for a deep understanding of the core concepts, the interrelationships between various elements, and the ability to interpret the information presented.

What Is a Balance Sheet?

A balance sheet is a fundamental financial statement that provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time, usually at the end of a fiscal year or accounting period. It shows the assets a company owns, the liabilities it owes, and the equity available to cover any debts.

It is the most important tool that helps investors and creditors assess a company’s ability to meet its financial obligations and achieve its long-term growth objectives. It provides valuable insight into a company’s liquidity, solvency, and financial performance. For example, a company with a high debt-to-equity ratio may be considered risky or financially unstable because it has a large amount of debt relative to its equity. On the other hand, a company with a high cash balance and low debt may be in a strong financial position, indicating that it can weather short-term setbacks and invest in future growth opportunities.

A balance sheet also provides a way for investors and creditors to evaluate a company’s efficiency in managing its assets, as well as its profitability. By comparing a company’s assets and liabilities, investors and creditors can determine how well the company is using its resources to generate profits. Lenders also use the balance sheet to evaluate a company’s creditworthiness and determine whether it can repay its debts. Ultimately, a balance sheet provides critical information that helps decision-makers assess a company’s viability and potential for future success.

Why Is a Balance Sheet Important?

The balance sheet is crucial for any business because it helps people understand the company’s financials. Understanding a balance sheet is essential for all stakeholders who require critical information about a company’s financial health and stability.

To summarize, here are the 5 main reasons why the balance sheet is important:

- Assessing financial health: The balance sheet shows a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity, providing valuable information to stakeholders about its financial health. By analyzing the balance sheet, investors, creditors, and other interested parties can determine whether the company is financially stable.

- Evaluating liquidity: The balance sheet also gives insight into a company’s liquidity, or its ability to meet short-term obligations. By comparing current assets (such as cash and accounts receivable) with current liabilities (such as accounts payable), stakeholders can determine if the company has enough liquid assets to cover its short-term debts.

- Tracking changes over time: By comparing balance sheets from different periods, stakeholders can track changes in a company’s financial position over time. This can help identify trends, such as increasing debt levels or declining profitability, which can inform future business decisions.

- Making informed decisions: The balance sheet provides a wealth of financial information that can help investors and business owners make informed decisions about investments, financing, and other strategic choices. For example, if a company has excess cash on its balance sheet, it may choose to invest in new assets or pay off debt.

- Compliance with regulations: Many companies are required by law to provide a balance sheet in their financial reporting. Compliance with these regulations is mandatory, and failure to do so can result in legal and financial penalties.

Components of a Balance Sheet

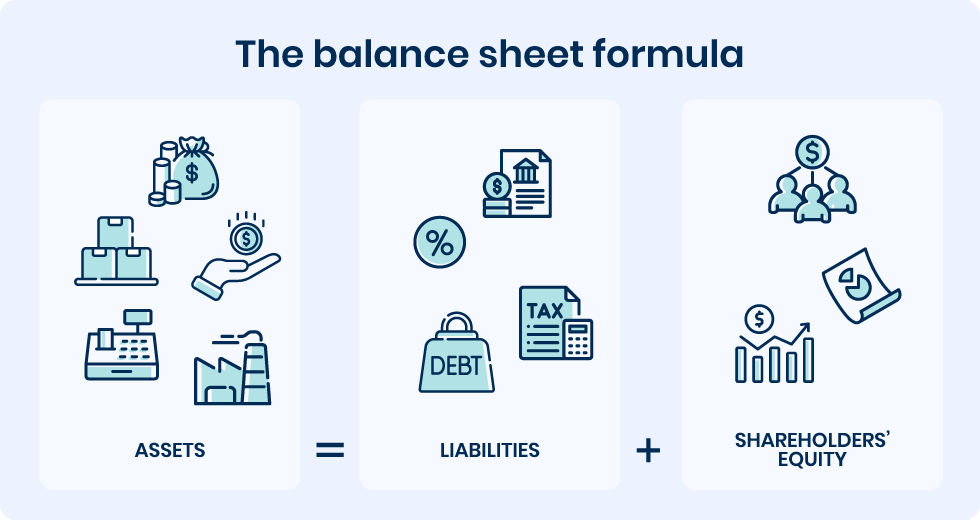

A balance sheet shows the company’s assets, liabilities, and equity, and how they relate to each other. The balance sheet is based on the accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This means that the total assets owned by a company must be equal to the sum of its liabilities and equity. So, the balance sheet is divided into two sections: the assets section and the liabilities and equity section.

Assets are resources that a company owns or controls, such as cash, investments, inventory, equipment, and real estate. The assets section lists all of the company’s current and non-current assets.

Liabilities are financial obligations that a company owes to its creditors, suppliers, employees, or other stakeholders, such as loans, taxes, utilities, and salaries. The liabilities include all of the company’s current and non-current liabilities, such as accounts payable, loans payable, accrued expenses, and long-term debt.

Shareholders’ equity reflects the amount of financing that is provided by the company’s shareholders or earnings that can be reinvested in the business. The equity section of the balance sheet includes common stock, retained earnings, and any other equity accounts.

Current Assets

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Marketable securities

- Accounts receivable

- Inventory

- Prepaid expenses

Current assets are a category of assets listed on a company’s balance sheet that are expected to be converted into cash or consumed within either one year or the normal operating cycle of the business, whichever is longer. These resources represent ones that are readily available and can be easily liquidated, providing the company with short-term liquidity.

Cash and cash equivalents

Cash is the most liquid of all assets and can be used to cover immediate expenses or pay off short-term debts. Cash equivalents, such as money market funds, certificates of deposit, and treasury bills, are short-term investments that can be quickly converted into cash. Companies need to keep adequate cash and cash equivalents to meet their short-term obligations, such as paying bills, meeting payroll, or funding unexpected expenses.

Marketable securities

These are investments in stocks, bonds, or other securities that can be easily sold to generate cash. Marketable securities are similar to cash equivalents but are slightly less liquid. They provide a way for companies to earn returns on excess cash while maintaining relatively low risk. Marketable securities can be bought and sold quickly, which makes them useful for covering short-term cash needs or taking advantage of investment opportunities.

Accounts receivable

Accounts receivable represent money that is owed to the company by customers who have purchased goods or services on credit. When a company extends credit to customers, it creates an account receivable, which is recorded as an asset on the balance sheet. Accounts receivable are usually collected within a few weeks or months, depending on the terms of the credit agreement. Companies need to monitor their accounts receivable closely to ensure that they are collecting payments on time and managing their cash flow effectively.

Inventory

Inventory refers to all of the company’s products that are ready for sale or in the process of being produced. Inventory can include raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods. Companies need to manage their inventory carefully to ensure that they have enough products to meet customer demand while avoiding excess stockpiles that tie up cash and increase storage costs. The value of inventory is recorded on the balance sheet at cost, which includes all of the direct and indirect costs of producing or acquiring the inventory.

Prepaid expenses

Prepaid expenses are payments made in advance for goods or services that will be received in the future. Examples include prepaid insurance, rent, or advertising costs. Companies may choose to pay for these expenses in advance to take advantage of discounts or lock in favourable terms. Prepaid expenses are recorded as assets on the balance sheet and are gradually expensed over time as the related goods or services are received.

Fixed Assets

- Plant, Property, Equipment

- Intangible Assets

Fixed assets are long-term assets held by a company that are not intended for sale in the ordinary course of business. These assets are employed in the production or delivery of goods and services, and they have a useful life that extends beyond one year. Fixed assets include both tangible assets, such as buildings, machinery, vehicles, and land, as well as certain intangible assets like patents and copyrights. They are recorded on the balance sheet at their original cost minus accumulated depreciation, which reflects their historical value and gradual deterioration over time. Fixed assets are important because they represent a significant investment for most companies, and play an important role in determining a company’s return on investment (ROI) as well as their ability to generate future earnings.

Plant, Property, Equipment (PP&E)

PP&E category includes all of the company’s physical assets that have a useful life of more than one year and are used in the production or sale of goods or services. Examples of PP&E include buildings, machinery, vehicles, furniture, and computer equipment. These assets are recorded on the balance sheet at their initial cost, less accumulated depreciation. Depreciation is a way of spreading the cost of the asset over its useful life and is recorded as an expense on the income statement.

Intangible Assets

These are non-physical assets that provide economic value to a company but do not have a physical presence. Examples of intangible assets include patents, trademarks, copyrights, goodwill, and customer lists. Intangible assets are recorded on the balance sheet at their initial cost, less accumulated amortization. Amortization is similar to depreciation, but is used for intangible assets instead of physical assets. Intangible assets can provide long-term value to a company by giving it a competitive advantage, protecting its intellectual property, or creating brand recognition.

Current Liabilities

- Accounts payable

- A portion of long-term debt

- Current debt

Current liabilities are obligations or debts that a company is expected to settle within one year, or the normal operating cycle of the business. These represent short-term financial obligations that need to be paid off in the near future. Common examples of current liabilities include accounts payable, short-term loans, accrued expenses, and dividends payable.

Accounts payable

Accounts payable (AP) refers to money that the company owes to its suppliers or vendors for goods or services that have been purchased on credit. Accounts payable are typically paid within 30-60 days, depending on the terms of the credit agreement. Companies need to manage their AP carefully to ensure that they are paying their bills on time and taking advantage of any discounts or incentives offered by suppliers.

A portion of long-term debt

This represents the portion of long-term debt that is due within the next year and is therefore classified as a current liability. Long-term debt includes loans, bonds, or other debt instruments that have a maturity date of more than one year. By breaking down long-term debt into current and non-current portions, companies can better manage their cash flow and ensure that they are able to meet their debt obligations.

Current debt

Current debt includes all of the company’s short-term debt obligations, such as lines of credit, credit card debt, and other loans that are due within the next year. These debt obligations are usually paid off using cash generated from operating activities.

Long-term Liabilities

- Long term debt

- Deferred tax

Long-term liabilities are obligations or debts that a company is expected to settle over a period exceeding one year. Unlike current liabilities, which are short-term in nature, long-term liabilities represent financial obligations that extend beyond the next year and reflect the long-term financing and capital structure of a company.

Long-term debt

Long-term debt represents borrowed funds or financial obligations that have a maturity period of more than one year. Long-term debt often includes loans, bonds, mortgages, and other forms of financing that provide a company with capital for long-term investments, expansions, or ongoing operations. Managing long-term debt is crucial for businesses, as it impacts their financial leverage, interest expenses, and overall financial health.

Deferred tax

Deferred tax refers to taxes that have been accrued but not yet paid. Deferred taxes are usually the result of differences between the tax basis and financial reporting basis of certain assets or liabilities. For example, a company may have a tax loss carryforward that it can use to offset future taxable income. The deferred tax asset that arises from this loss carryforward is recorded as an asset on the balance sheet. Conversely, if a company has taken accelerated depreciation for tax purposes, but slower depreciation for financial reporting purposes, it will record a deferred tax liability to account for the difference.

Shareholders’ Equity

- Retained Earning

- Share capital

Shareholders’ equity, also known as stockholders’ equity or owners’ equity, represents the ownership interest of the shareholders in a company’s net assets. Shareholders’ equity is calculated by subtracting total liabilities from total assets and consists of various components, including common stock, additional paid-in capital, retained earnings, and accumulated other comprehensive income. It serves as a measure of a company’s net worth and represents the value that would be returned to shareholders if all liabilities were settled.

Retained earnings

Retained earnings are cumulative profits that a company has earned over its lifetime, less any dividends paid to shareholders. Retained earnings are recorded on the balance sheet as part of shareholders’ equity and are used to fund future growth opportunities, pay down debt, or distribute dividends.

Share capital

Share capital is the funds that a company raises by issuing shares of stock to investors. Share capital is recorded on the balance sheet as part of shareholders’ equity and represents the ownership stake that investors have in the company. Shareholders may receive dividends or participate in the company’s growth through increases in share price.

How To Read a Balance Sheet

- Begin with the assets section. Analyze the different categories of current and fixed assets. Pay attention to the values assigned to each category, as they reflect the company’s resources and ability to generate future revenue.

- Move on to the liabilities section. Identify the types of liabilities, including current and long-term liabilities. Assess the magnitude of the liabilities to gauge the company’s financial obligations and potential risks.

- Explore shareholders’ equity. Examine the components of shareholders’ equity, such as common stock, retained earnings, and accumulated other comprehensive income. This section reveals how much the shareholders have invested and how the company has performed over time.

- Calculate important financial ratios based on the information in the balance sheet. Ratios like the debt-to-equity ratio, current ratio, and return on assets can provide insights into the company’s solvency, liquidity, and profitability.

- Look for any significant changes or trends. Compare the current balance sheet with previous periods or industry benchmarks to identify areas of improvement or concern.

- Pay attention to footnotes or accompanying disclosures, as they provide additional information about specific assets, liabilities, and accounting policies used in preparing the balance sheet. These footnotes can enhance your understanding and provide context for certain line items.

- Understand the industry-specific nuances that may impact the interpretation of the balance sheet. Different industries have varying asset and liability structures, and it is important to consider these industry-specific factors when analyzing a balance sheet.

- Interpret the balance sheet holistically, considering all the information and ratios analyzed. Look for strengths, weaknesses, and potential red flags that may impact the company’s financial stability, growth prospects, and overall value.

How To Interpret Balance Sheet With Cash Flow and Income Statements?

Here are some tips for how to use the balance sheet with other financial statements:

- Use the income statement to analyze a company’s profitability: the income statement reports a company’s revenues, expenses, and net income over a specific period of time. By analyzing the income statement alongside the balance sheet, you can gain insight into how profitable the company is and how well it is managing its expenses.

- Use the cash flow statement to analyze a company’s liquidity: the cash flow statement reports a company’s cash inflows and outflows over a specific period. To understand how well a company is handling its cash flow and if it can satisfy its short-term requirements, you can examine the balance sheet and the cash flow statement together.

Analyzing the balance sheet in conjunction with other financial statements can provide insight into a company’s overall financial position, including its liquidity, solvency, and ability to create long-term value for shareholders.